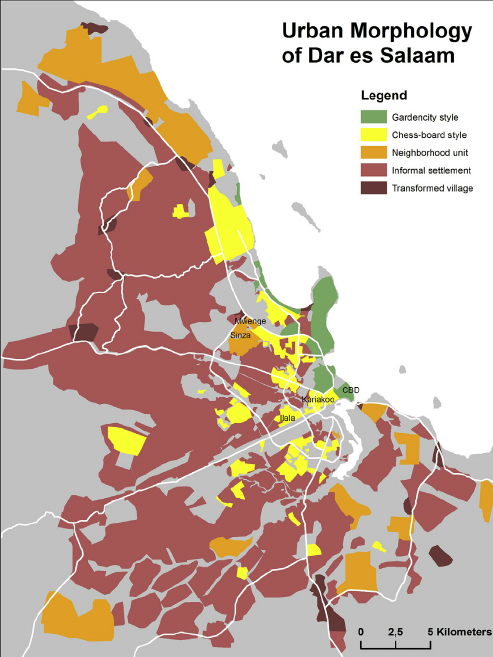

Take a look at this image. On one side are precisely organised streets, populated by nicely cut trees and homes with swimming pools. On the other side is a clutter of tin roof houses, chaotically structured and built so close to each other one can imagine that neighbours can hear one another breathe.

Masaki, the area on the right, is considered to be one of the wealthiest suburbs in Dar es Salaam. A few kilometres away, on the other side of the road is Msasani, a less affluent part of the city. They are, visually at least, a picture of inequality. The image raises a number of questions. We chose to focus on one: Does being born in Masaki afford you a better chance in life than growing up in Msasani?

Two very different lives

This issue hovers over our conversation with Hassan, a 12-year standard 5 student living in Msasani. Hassan lives with his mom, grandmother and two siblings. He wakes up at 6 o'clock every weekday morning and walks to school and he makes sure he is there right before the morning bell rings at 6.30am. If it's a Monday he will stand with his mates and sing the national anthem. By 8am, he joins 45 other kids and four teachers at his standard 5 class where he will spend the next six hours trying to learn.

“I want to be good in English so that when I become a professional football player and go play abroad, I can communicate better.”

Hassan likes school. He says he is a top ten student and his grades average between 60–70%. His favorite subject is English. Not because he wants to be a writer or an English professor. He has bigger goals than that.

“I want to be good in English so that when I become a professional football player and go play abroad, I can communicate better,” he says.

But professional football is not the only thing that Hassan aspires to. While he does not know a lot of people who have a higher education, a young female university student, who rents out a room at his house, has inspired him to also want to go to university.

“I haven’t told anyone, even my mom, but I want to go all the way to university,” he says.

A few kilometres away, we meet Saida.* She is 14 years old, in grade 8 (equivalent of Form II) at a private school in Masaki. Saida, like Hassan, wakes up early, typically around 6 o’clock every morning and is driven to school and gets there around 7.30 am for an 8.45 am start of classes.

Over the course of the day — which ends at 3:15 in the afternoon — she joins 6 other classmates for 6 classes that includes Maths, French and Digital Design, a tech class. Saida describes herself as an average student. She says Drama is her favourite subject. “It’s very creative, and it gives me a lot of ideas,” she says.

Saida’s true passion is in fashion and design. “I like playing around with clothes, I try to make up any style that I can,” she says. It doesn’t necessarily mean that fashion will be what she ends up doing as a career. She has also thought about medicine and law.

“I like lawyers,” she says. “Every year our minds change, what we want to do, so my goals also might change.”

She points out that while her dad gives her and her three siblings the freedom to pursue their own choices, he expects them, like himself to go to university.

“He wants us to study and be really independent in life,” she says.

Saida says she likes to travel and hopes one day to travel the world. She goes to school to learn and get knowledge. “Grow up and be something good,” she says.

Now, it is important to note that just because Hassan grew up in Msasani it does not mean that he is unlikely to realise his aspirations. Just as Saida being born in Masaki is not a guarantee that we will be seeing her strutting her designs at the Milan fashion show. Both these young people clearly want to "be something good" in life. And the fact that Hassan has a few more obstacles to overcome than Saida, may steel him for the task ahead. But the issue is whether the accident of his birth disadvantages him in comparison to Saida. And evidence suggests that it does.

Dense informal settlements like Tandale mean long commutes, less opportunity, and less access to economic mobility. Photos by Johnny Miller / africanDRONE

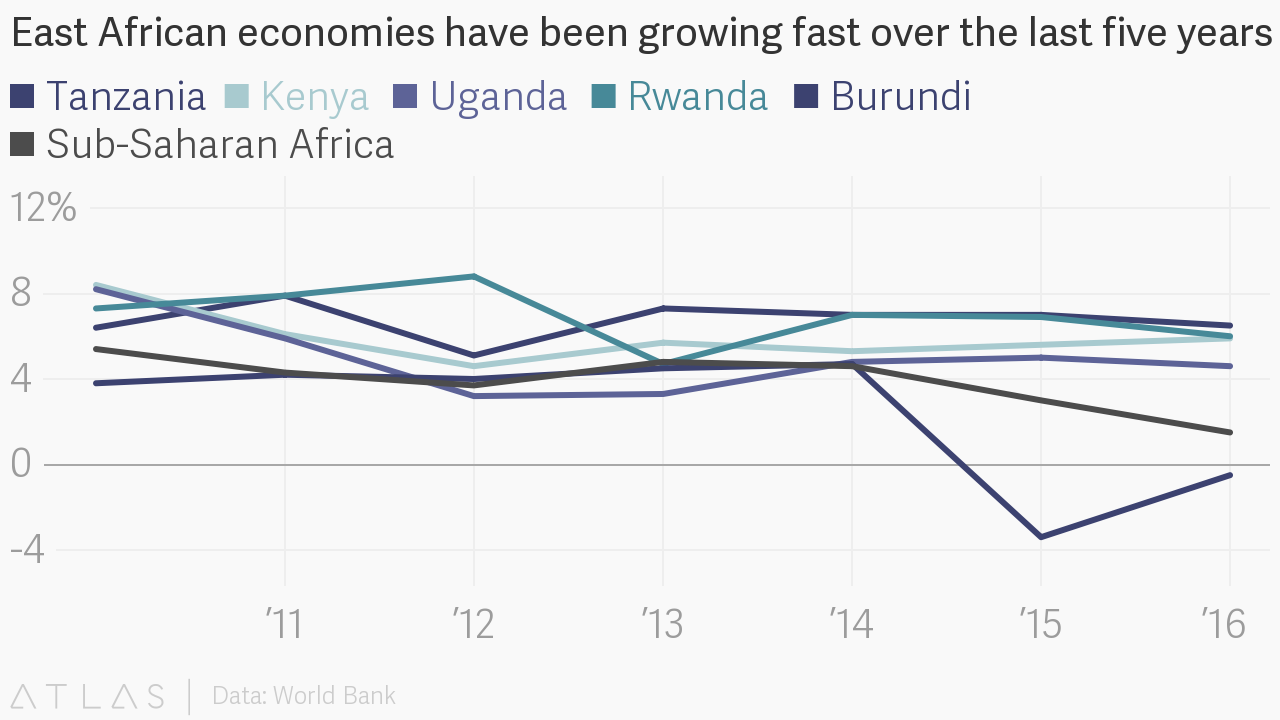

Economic growth

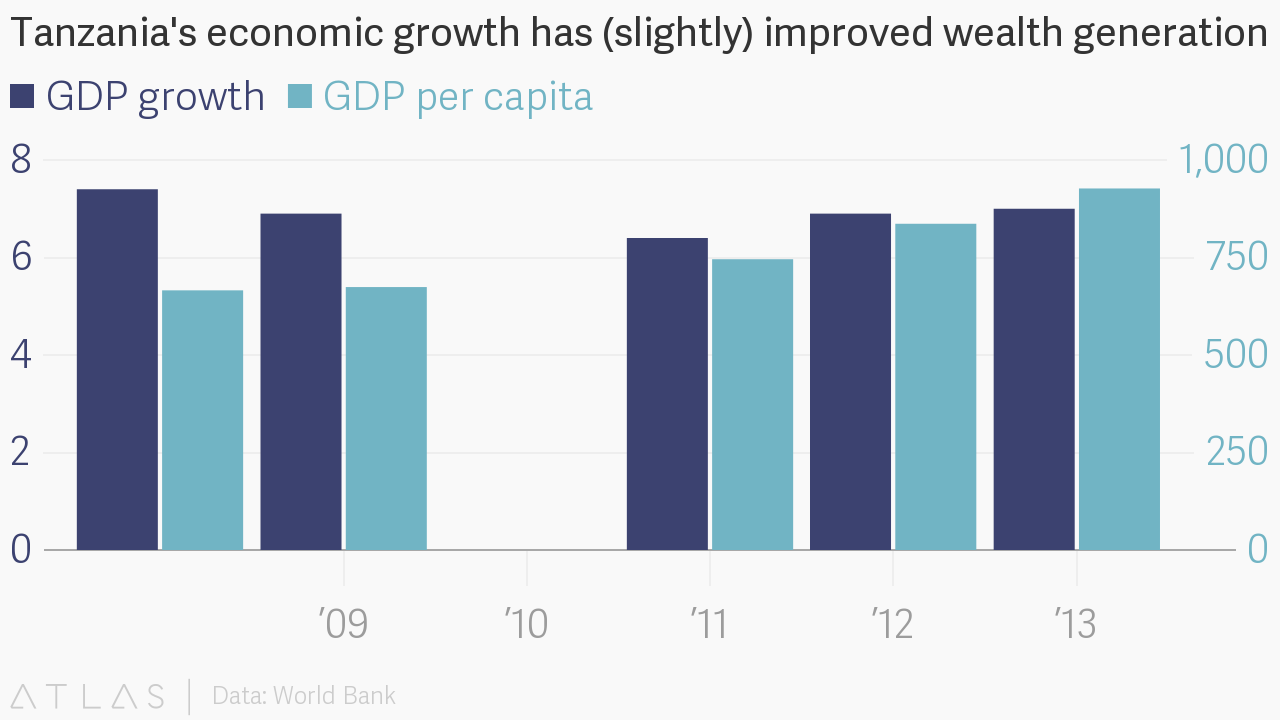

Around Dar es Salaam, the country’s commercial capital, evidence of economic activity abound. From the skyscrapers that have shot up over the last few years to the ubiquitous use of mobile phones, Tanzanians appear to be reaping the rewards of a fast growing economy.

While seeing is not necessarily believing, evidence does suggest that the 6–7% economic growth the country has enjoyed has had an impact beyond the shiny new buildings populating Tanzania’s great metropolis.

Wealth per capita, which is the average assets owned by an individual, grew by 92% since the year 2000, from $250 then to $480 in 2015.

While 12 million people, over a quarter of the population, live on 1,300 shillings ($0.60) a day, the poverty rate in the country has fallen from 60% in 2007 to about 47% in 2016 when measured by the $1.90 a day global poverty line. Basic needs poverty dropped by 6% to 28% percent between 2007 and 2011/12 while extreme poverty fell by 2% in the same time span.

Other metrics also show improvement in the overall well-being of Tanzanians. The quality of housing Tanzanians live in, another yardstick to judge reduced inequality, has got better.

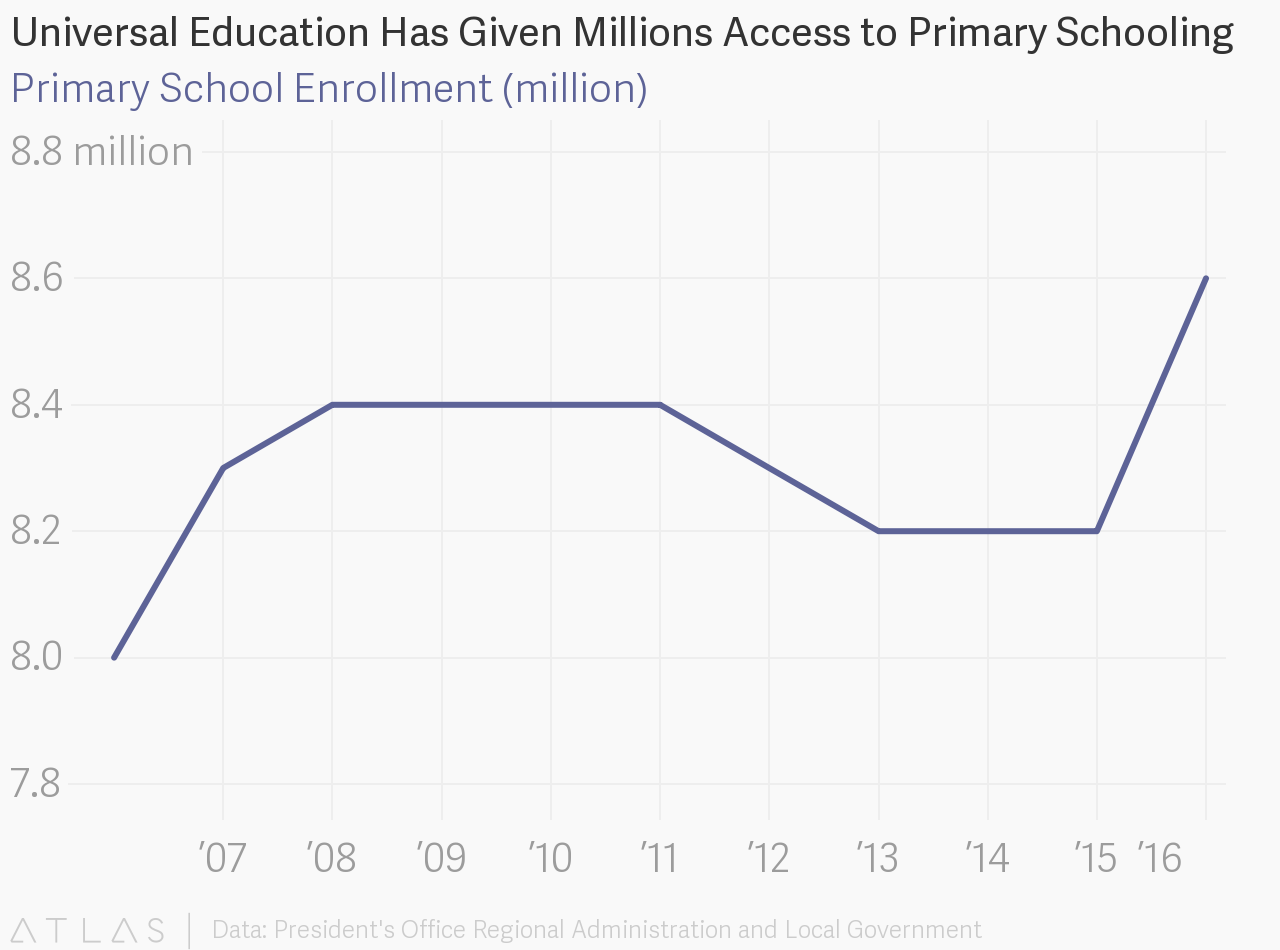

School enrolment numbers have also shown progress.

The question is whether this poverty reduction and wealth creation is offering the kind of social mobility to help children like Hassan climb the social ladder.

And there is indication that things are not moving fast on the social mobility front.

Economic mobility is difficult for those in Dar es Salaam's less affluent communities. Photo by Johnny Miller / africanDRONE

From 2007 to 2012, about a third of the country’s 50 million people were able to lift themselves to a higher welfare class, according to the World Bank. However, during the same time, 13% of the population slipped into the bottom 25% of the income distribution scale with 12% of the poor stuck in chronic poverty.

All this suggests that, despite the progress East Africa’s second largest economy has made in tackling poverty, its still significantly tough to bootstrap yourself out of a lower economic class.

A contemporary map shows how the city fabric is still very much in place from colonial times.

Translation of urban planning models: Planning principles, procedural elements and institutional settings Article · Aug 2015 · Habitat International

Education, Education, Education

Economists agree education can play a crucial role in enabling those from lower economic classes to rise to a higher station.

In Tanzania, evidence suggests that those with a tertiary university education are likely to earn more than those with lesser educational qualifications. In a 2015 earnings survey by the National Bureau of Statistics, 74 percent of newly recruited employees with tertiary university education had a starting salary of from 500,000 to 1,500,000 shillings compared to only 8 percent of those with a secondary education.

The way education is structured in Tanzania, however, reinforces inequality, analysts say. Kids that go to public schools rarely interact with their counterparts in private education, creating social divisions on top of disconnection in opportunities.

"The type of education one gets factors in a lot when it comes to inequality," Aikande Kwayu, an education policy analyst, says. "The returns on education are very high, especially those who receive a high quality education, when it comes to employment, business."

The government has tried to address some of the intrinsic inequalities that exist in the country. Implementation of universal access has helped millions of children get an education. The country has also seen pass rates at secondary level improve, where in 2015, 68% of those that sat the national exams passed. Additionally, transition rates from primary to secondary is also high with 61% of government students enrolling in form 1, government data shows.

From a policy perspective the government understands that access to education helps in fighting inequality, Kwayu says. The challenge, however, is that access alone is not enough, Kwayu says.

"The policy focuses on input -- enrolment, desks, etc -- but what about actual learning and skills development?" asks Kwayu.

Looking at Hassan and Saida, for example, a gap in skills can already be seen to be emerging, despite both having access to education. Saida is learning French and Digital Design, an information technology subject, subjects that are currently not available for Hassan. These subjects are preparing Saida for the contemporary and future world, a world that is global and more tech driven, in a way that she can potentially compete with her peers around the world.

But don't count out Hassan just yet. His ambitions may just surprise.

"One day I will play at Manchester City and score goals like [Sergio] Aguerro," he says.

In Tanzania, evidence suggests that those with a tertiary university education are likely to earn more than those with lesser educational qualifications. In a 2015 earnings survey by the National Bureau of Statistics, 74 percent of newly recruited employees with tertiary university education had a starting salary of from 500,000 to 1,500,000 shillings compared to only 8 percent of those with a secondary education.

Other factors, like luck and hard work do come into play when it comes to where someone ends up in life but education remains the difference maker in overcoming a life of poverty.

“While getting an education is not a guarantor of upward social mobility, without it, you don’t even get onto the lowest rung,” Aidan Eyakuze, an economist and executive director of Twaweza, a civil society organisation that works on education issues in East Africa, says.

The quality of education children receive increasingly is being shaped by the ability of parents to pay for it. This means that the starting point, the social class into which a kid is born, is becoming crucially important to their prospects going forward.

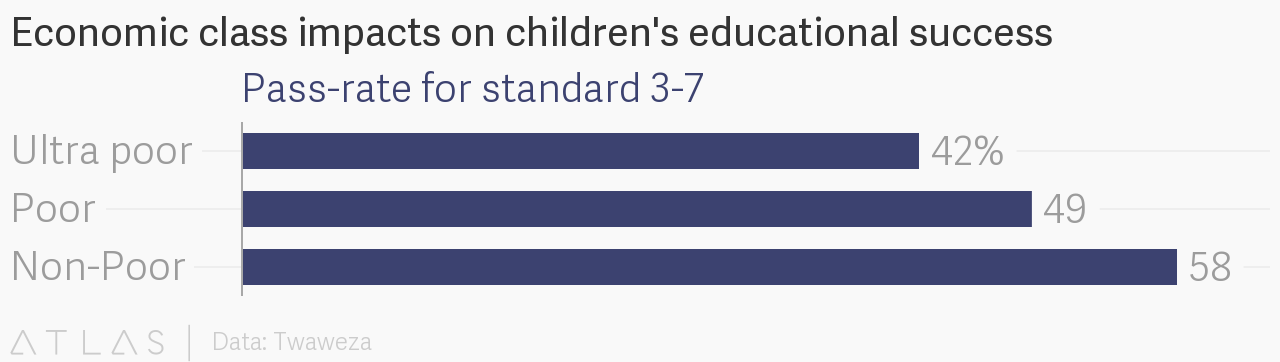

“Economic class is having an increasingly important effect on social mobility,” Eyakuze says.”

Poverty reduction gains Tanzania has seen over the past few years is helping somewhat in leveling the opportunity field for children who come from more humble backgrounds. They are healthier and their parents can afford to finance better quality education that give them a chance to compete with their more well-off compatriots.

“The task for government is to maintain and expand that opportunity space as much as possible to unleash and nurture Tanzanian’s initiative and risk-taking instincts,” Eyakuze says. “And the investment in education, with a focus on learning, not only inputs such as desks and teachers, will yield the most important individual and social dividends for the country.”

Primary School Students at a Public School in Dar es Salaam. Photo by Emanuel Feruzi / Code for Tanzania

As I chat to Hassan, a question hovers that we don’t discuss: what are the chances that he, and his fellow students in Msasani, will fulfil their dreams of becoming doctors, teachers, athletes, engineers and all the other professions that kids his age may aspire to be.

How much is where he comes from a factor in his future success? Does his economic and social background play a role? And is Tanzania’s 6–7% economic growth over the last decade opening up the field of opportunities for Hassan and his friends?

One's background does have an effect on the ability of those less affluent to build up wealth, says Kwayu, the education policy analyst. And structural issues in the economy make it even tougher to overcome such a background.

"If you come from a more affluent background, it means that you have access to more capital, which means more income than labour and therefore there will be more inequality compared to someone who starts off with no capital," she says.